Literature Review

Broad security study of Tuya-based devices

In 2018 the security research group @{MichaelSteigerwaldVTRUST-2018} analysed a line of white-labelled IoT product revisions based from the IoT manufacturer Tuya. Despite claims of ‘military-grade security’, basic packet logging of network activity concluded that “the analysis of the ‘smart’ devices using this basic platform is generally frightening”, with “serious […] shortcomings”. It was revealed that various PII, encryption keys and the device’s serial number (used to target a specific device through remote commands) were insecurely transmitted over the network, allowing a malicious user on the same wireless network to eavesdrop on the communication. Furthermore during the initial setup and pairing of the IoT device, wireless credentials were also insecurely transmitted in plain text, allowing wireless network credentials to be observed.

VTRUST commented on the dangers of vendors selling white-label products, where anyone could become a so-called ‘IoT company’ regardless of whether they had “in-depth technical knowledge of IoT or IT security”. As a result of the hands-free approach to security and privacy for both direct and indirect customers of the IoT platform, concerns are raised regarding the ease of possibly distributing maliciously modified devices, where firmwares could be tampered at any stage during the supply chain. It is important to recognise that most custom firmware releases or so-called “hardware hacks” originated from the desire to decouple hardware from online and official cloud services. These ventures effectually disconnect internet-reliant devices from the cloud, and limit their connectivity to a local server where communications are transparent and minimal.

As a result of many Tuya-powered devices using the widely popular Espressif ESP8266 SoC, VTRUST was able to exploit discovered vulnerabilities to perform over-the-air upgrades of custom firmware such as ESPhome and Tasmota. An automated flashing tool (tuya-convert) was released, allowing consumers to easily integrate these devices with local home automation software such as HomeAssistant. As a result of VTRUSTS’s findings, the overall security posture of modern Tuya-powered devices has since improved1, with implementations of local flash memory encryption and firmware signing measures during over-the-air firmware upgrades.

VTRUST’s technical findings offer insights into methods of network-level security assessment highlighting how easily an individual could their own IoT company, and the possibility of reselling devices with modified firmware with malicious intent.

Broad security study of Xiaomi-based devices

@{DennisGiese-2019} performed a security assessment over a broad range of Xiaomi’s IoT products to examine the overall ecosystem security. Through different keystroke injection methods, UART commands and hardware fault injection techniques, Giese obtained shell access into various Xiaomi-powered devices. It was concluded that due to the enormous size of Xiaomi’s ecosystem, it was difficult to enforce global security policies between the different vendor-provided plugins that continued to supported deprecated functions and APIs that were still being used by legacy devices. From this research, a Xiaomi cloud emulator was built, allowing for complete offline functionality and control over a large range of Xioami devices without internet connectivity. This research also paved the way for other third party software to be developed, such as Valeduto - which provides a feature-rich web interface to operate a robot vacuum cleaner.

He concluded that Xiaomi indeed treats their security concerns seriously, given their quick responses to reported security incidents and vulnerability reports. During this study, the security of the Roborock S6 vacuum cleaner was also assessed - albeit briefly. As such this thesis will not only further explore the security posture of the Roborock S6 since 2019, but to also audit the state of privacy of the device.

Security study of smartphone applications

@{tibav:36251} investigated the security claims of a smart doorlock which boasted in bank-grade security, overall better security over conventional lock and key systems. These claimed were however invalidated, as various flaws within the smartphone application were discovered, allowing control over lock settings that were only protected by client-side checks. Consequently, modified request payloads containing elevated authorisation claims would be naively accepted by the server, allowing lock settings to be modified by a guest or limited user. Furthermore, various debugging menus were present in the production version of the smartphone application, allowing certificate pinning protections to be subverted. In addition, the privacy of the user was also questioned, as it was observed that door lock events and other identifiable information were being transmitted to a logging endpoint.

The vulnerabilities in the smart doorlock’s own product security highlight the importance to verify claims that manufacturers may advertise. This study serves as an excellent example a poorly access control system, where novel methods of HTTP request tampering, hardcoded keys and insufficient keyspaces allow for the arbitrary privileged control of the smart doorlock. Subversion of HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) and certificate pinning policies through system-wide tools2, per-application patching3 or accessible debug menus furthermore underlines that certificate pinning should not be relied upon to verify identity nor authority.

Analysis of similarities in IoT firmwares

@{184449} performed a broad static analysis over a large number of firmware images to identify common patterns and similarities between firmwares of different product vendors. During the analysis of the 693 images, 38 new vulnerabilities were discovered, some which were present in the majority of images. A large number of hardcoded keys and credentials were also discovered that could render the IoT device or its infrastructural service vulnerable. To facilitate the similarity analysis of firmware images, where per-byte analysis techniques are nonsensical, tools like binwalk, ssdeep, and sdhash were employed - which helped to facilitate file exploration relative to their file type and architecture. To compare versions of the same binary across different firmwares, a tool called BinDiff was used, which would compare similarities and differences in disassembled code.

A large proportion of images shared similarities in code execution graphs, indicating that many vendors had simply reused and repurposed sample code (often available as part of a SoC’s SDK). Whilst sample code itself is not often vulnerable, given the commonality of other vulnerabilities, concern is raised as to the vendor’s technical capability and understanding of IoT systems and of security. The tools and methods to perform this firmware study are transferable to the scope of this thesis.

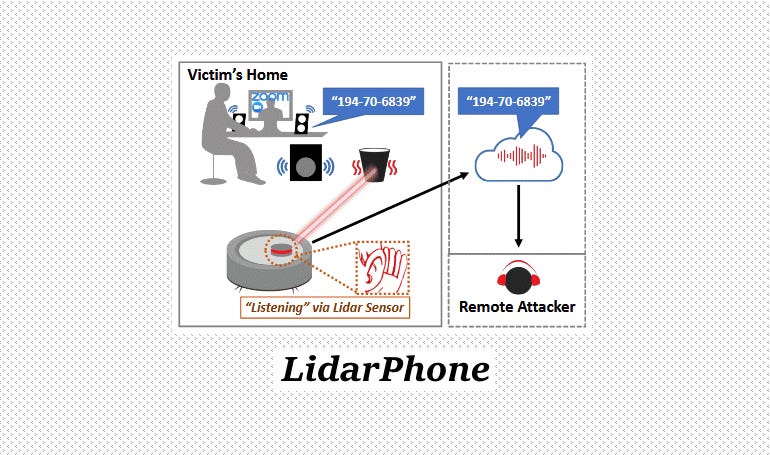

Side-channel application of LIDAR sensor measurements

As more and more IoT devices become online and sensor data is transmitted around the world, there are growing concerns to thoroughly investigate the extents of what data can be retrieved from the sensors. Given that the outputs of Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) sensors are intensity readings and distance measurements, @{10.1145/2789168.2790119} developed a method to translate the intensity readings from the LIDAR sensor back into audio singles, when the LIDAR sensor was directed towards a surface near an audio source. This allowed speech to be identified from micro-vibrations within objects, prospectively raising concern regarding the privacy and confidentiality of sound in a sound-proof room.

This research has since been continued and tested on robot vacuum cleaners which too incorporate LIDAR sensors intended for spatial mapping. As general off-the-shelf LIDAR sensor units are used within vacuum cleaners, light intensity values were also returned by the sensor, and could be used to in a similar fashion to detect speech and sound [@10.1145/3384419.3430430]. In the application of a robotic vacuum cleaner, light intensity values are considered a side-channel concern as those readings are not required for the operation of a vacuum cleaner. Despite integration limitations of sampling intensity values on a vacuum cleaner (i.e. accounting for the continuous rotation of the LIDAR sensor and noise floor as a result of the vacuum engine), a classification accuracy of 91% was achieved when extracting sensitive data such as digits of a credit card.

Whilst this thesis will not pursue the exploration of sensor data analysis, these two studies offer potential future research areas on privacy concerns surrounding robot vacuum cleaners, as newer revisions of smart devices become continually equipped with more accurate and feature-rich sensor.

Shell access via sideloaded media

Often as a necessary preliminary step to further research, modification and integration of proprietary technologies, many device rooting methods (i.e ways to gain elevated access to a device) have been publicly disclosed on the internet. Commonly, devices that may not be expected to have outbound internet connectivity may provide offline firmware upgrade functionality by executing a script, or booting from some form of removable flash memory such as an microSD / SD card. @{EliasKotlyar-2017} demonstrated the ability for the inexpensive Xiaomi Dafang WiFi Camera to boot into a custom alternate u-boot bootloader flashed onto a microSD card. Through UART headers located on the device’s circuit board, the boot environment was modified to start a shell (/bin/sh) instead of the original entry-point script, effectively rooting the device. Kotlyar was then able to dump the firmware, later producing a custom firmware release that did not rely on the vendor’s cloud infrastructure.

Through the subversion of interrupting the default boot sequence, access to a shell allowed for the development and release of decoupled software. Whilst the exact rooting steps are unlikely to be directly transferable to other devices, the idea of obtaining elevated access via sideloading techniques is an important method to investigate.

Shell access via BGA pin shorting

For devices that do not automatically boot into removable media, methods have been discovered to force certain SoC’s to enter a recovery or fallback mode. Allwinner-based SoCs implement a mode known as “FEL” that can be entered by pulling a certain pin LOW during boot4, which allows device manufacturers to perform initial image flashing and bootloader configuration. For developers and hardware hackers, FEL mode allows users to modify the boot environment to execute a shell, allowing for further post-exploitation methods and firmware dumping / analysis.

It is noted that FEL mode can also be entered if the SoC fails to successfully launch the bootloader. @DennisGiese-2019 identified this fact and exploited the physical pin layout of the Allwinner R16 BGA package, where the data pins connecting the SoC to the (e)MMC chips (where the bootloader is stored) were on the physical perimeter of the SoC. By sliding a piece of aluminium foil (roughly 0.02mm thick) between the circuit board and the solder plane of the SoC (0.3mm), the electrically conductive aluminium foil could momentarily short the data pins long enough to cause the bootloader read operation to corrupt and fail, hence booting into FEL mode and eventually gaining shell access. This method is favourable when compared to pulling the FEL pin low during boot - as access to the FEL pin would require the desoldering and removal of the SoC from a circuit board - which can be tedious and potentially destructive.

Through this hardware fault injection technique of shorting data pins during boot, Giese was able to successfully gain access to a shell on Roborock’s first robot vacuum cleaner (Mi Robot Vacuum Cleaner). later

Giese noted that on the circuit board of the Roborock S7 vacuum cleaner, test pad TPA17 is connected to the ball grid location corresponding to the FEL pin - allowing FEL mode to be entered without performing a hardware fault injection.

Hardware based extraction of flash memory

In situations where no provisions exist to programmatically extract stored data from a system (i.e. shell access to perform disk imaging), hardware devices known as flash programmers can be used; where they are specially designed to read and write data on flash chips. Flash programmers however present a high cost overhead, as they are rather costly and only work with specific models and/or types of flash chips; rendering it infeasible to own a specific flash programmer for each possible variation of flash chip. @{JuanCarlosJimenez-2016} points out that a Raspberry Pi could be used as an affordable budget solution when paired with open source flash programming software like flashrom.

It is noted that the process of hardware flash chip dumping is not feasible in the scope of this thesis due to resource constraints of not possessing a suitable flash programmer, as well as the risk associated with hardware-based methods being possibly destructive with irreversible damage. Preliminary results (See chapter 5) have however suggested that firmware data can be obtained through programmatic methods, and as such this method will not be pursued.

Cold-boot attack to dump memory state

Regarding prior investigations of smart robot vacuum cleaners, @{238606} performed a security analysis on the Neato BotVac Connected robot. Through the combination of a cold-boot attack - where a system is rebooted without the volatile memory (i.e. RAM) being cleared - and the booting of a custom bootloader image, the memory state of the system’s prior execution was able to be dumped and analysed. This memory dump is of significant value as it would contain the binaries of loaded programs as well as their application state. The proceeding analysis revealed major vulnerabilities and concerns in the vacuum cleaner and more alarmingly, in Neato’s cloud infrastructure.

Whilst logs and coredumps were encrypted when transmitted to cloud servers, the encryption keys were discovered to be hardcoded which nullified any assurances of encryption. Authentication and authorisation tokens were all encrypted with the same static RSA key - which left the cloud infrastructure vulnerable to impersonated identities and access. Supposed randomly generated keys were also discovered to be vulnerable, due to the keyspace for entropy being so short that the key was able to be bruteforced within reasonable time. Furthermore, an unauthenticated endpoint on the robot vacuum cleaner’s remote port was found to be vulnerable to a buffer overflow, allowing remote code execution on the robot by anyone connected to the same wireless network.

The analysis of a system’s memory state is beneficial to the security assessment of a product’s firmware as static analysis techniques are unable to account for dynamic data such as response payloads from HTTP communications. It is however, unlikely that a cold-boot attack will be necessary in the scope of this thesis as preliminary results have already concluded that shell access is obtainable, hence other simpler methods could be performed to extract memory states.

-

https://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/Smart-Home-Hack-Tuya-veroeffentlicht-Sicherheitsupdate-4292028.html ↩︎

-

Generally triggered by pulling FEL pin (

LRADC0) LOW during boot ↩︎